Counting Coins at the U.S. Mint: Roger Burdette

By Roger W. Burdette, special to CoinWeek …..

The United States Mint has been turning out millions of circulation coins each year since about 1804. We collectors are familiar with coinage metals, planchet cutting, coin stamping, and the shipment of kegs and bags of coins. But one important subject is often ignored: How do all these metal bits get counted? How accurate were coin counts in the past? How long would it take to count one million 1804 cents?

This last question is the easiest to answer. If we assume someone could count three coins per second, then it would take one person almost 93 hours to complete the task. We could add more people, but that would increase not only labor expenses but also the number of lost and mishandled coins and the likelihood of other mistakes. The fewer coins handled, the better.

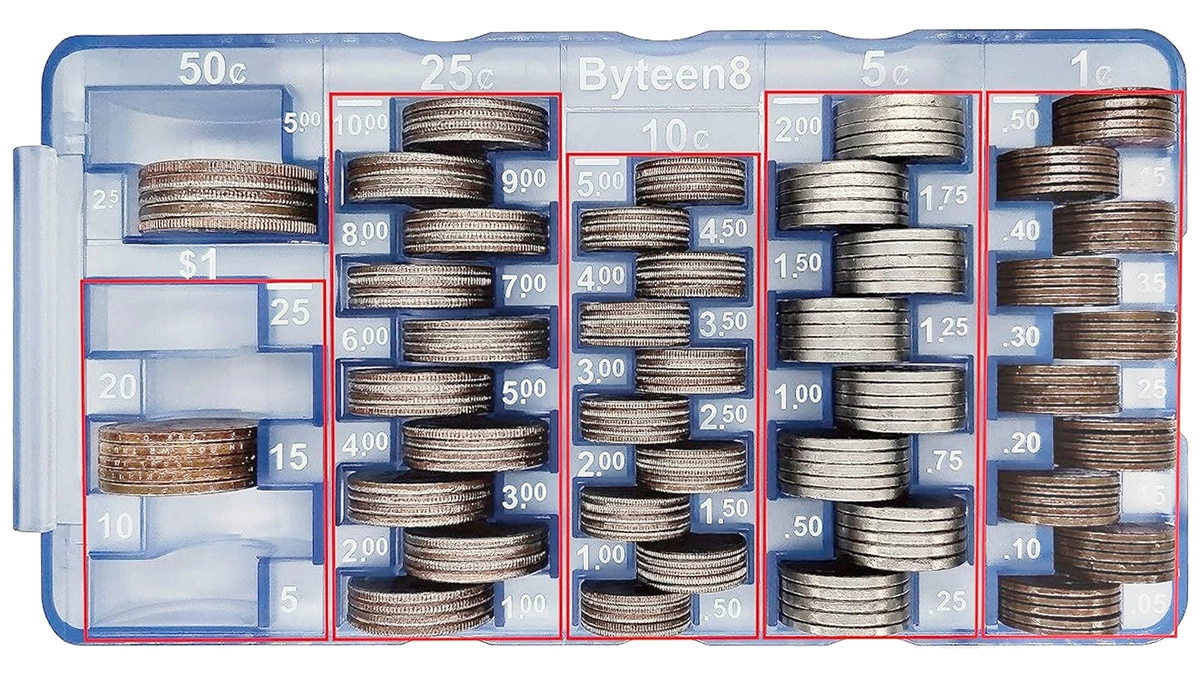

Counting coins by weight is good when individual weights can be tightly controlled. But that was not practical until planchets could be accurately sorted by weight. Coins could also be piled into stacks of 10 or 20 pieces, then similar height stacks quickly built to the first one. Again, this requires a uniformity of thickness that was not possible in the United States until after Melter and Refiner Franklin Peale’s mechanical innovations in 1834-37. Stacking could be used for small amounts of coin, such as in banks or individual merchants’ offices, but not for large quantities.

Wooden boards and stacking tubes were used by bankers and money changers to count coins for centuries.[1] These were better than individually counting coin stacks but still suffered from errors caused by irregular dimensions of pieces made by hammer, on screw presses, or without edge collars.

Improvements to coin-counting boards at the Philadelphia Mint were made by Peale in 1834. But an important change came in 1838 when New Orleans Mint Coiner Rufus Tyler invented an improved mechanism that was patented in the name of Rufus’ Estate by his brother Philos in 1841.[2] Tyler’s counting board was so efficient that the U.S. Mint paid his widow a licensing fee of four cents per 1,000 coins counted to use the patent.[3] In October 1844, Mrs. Tyler’s rights were bought by the Mint Bureau for $2,500.[4]

Tyler’s patent described a flat board into which low metal rails were fitted (B). The height of each rail was equal to the thickness of one coin. The space between rails (C) was equal to the diameter of the new coin of the specified denomination. The number of spaces (C) and the length of rails determined the quantity of coins necessary to fill the board. The patented board was 13×18 inches if used for half dimes and held 500 pieces in a grid of 20×25 pieces.

This brief article from The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal in 1854 describes the use and advantage of Tyler’s invention:

A Counting Board

It is very evident to all visiting the Philadelphia Mint that the large number of pieces, as were produced in 1853, could not be coined and manipulated by the limited number of employees without the aid of some labor-facilitating arrangements. One which is most worthy of remarks is the method of counting pieces coined – if counting it can be called, for in principle it is a measuring machine. The arrangement of this counting frame, or tray, may be understood from the following description of its construction.

A board or tray of such dimensions as may be required, is divided by a given number of parallel metallic plates inserted into its plane and slightly elevated above it. The edges of the metal plates rise no higher than the thickness of the coin for which it is intended. The board is of such a length as will hold a few more than the required number of pieces to be laid longitudinally in the rows. It is divided across and at right angles with the rows, and hinged at a point opposite to a given number. [Shown by pentagonal blocks at upper left and right corners.] One counting board employed by the coining department counted 1,000 pieces, that is to say, it had 25 parallel grooves or rows sufficiently long to receive 40 pieces.

$10 in cents within about 20 seconds. The narrow collecting slot funneled coins into a bag holder. This photo

was made in 1898. Image: Library of Congress. Colorized by CoinWeek.

Now, having thrown on this board a large excess of pieces, it is agitated by shaking until all the grooves are filled. It is then inclined forwards until all the surplus pieces have slid off, one layer only being retained by the metallic ledge. The hinged division [upper end of Figure 4] is then suffered to fall, which at once throws off all except the 40 pieces in the length of each row. This operation, somewhat difficult and tedious to describe, is performed in a few seconds, and results in retaining on the board 1,000 pieces, each piece exposed to inspection, and the whole accurately counted without the wearisome attention – so likely to result in error – required under usual circumstances.

The very large number of pieces coined during the last year (1853) has been counted almost exclusively by two female manipulators, assisted by a man who had the duty of weighing them in addition as a testing check. The same amount of labor by ordinary means could not have been performed with fewer than thirty or forty workers, to say nothing of inferior accuracy.[5]

To use a flat counting board with dividing rails, the worker put a scoop of coins on the board and pushed them around until the board was filled. Excess pieces were easily slid off the board. Defective pieces could be quickly identified and replaced. Counted coins were then dumped into a wooden bin until the desired total had been counted. A keg of large cents was customarily $70 or 7,000 pieces. Mint documents suggest it took about two-and-a-half minutes to fill a keg.

of coins fresh from the press room. Image: Library of Congress. Colorized by CoinWeek.

The largest flat counting boards held five hundred silver dollar pieces. An experienced operator could handle about 2,000 coins of any denomination per minute. As they were counted, they were placed in bags.

As coin dimensions became more consistent, counting boards were made with thicker borders so that coins could be counted in several layers at one time. The most common silver dollar boards were 10x25x1 coins or 250 pieces per count. Silver dollar boards were occasionally used that could count 10x10x5 coins, or half a bag of dollars weighing about 24 lbs.

closed as soon as filled. At this time there were three counting stations operated by seven workmen who were

paid $3.50 per day. Image: Library of Congress. Colorized by CoinWeek.

In day-to-day use, counting boards were faster than mechanical counters and caused much less abrasion on the coins. This was important for gold coins, whose weight was closely monitored. As late as 1917, Federal Reserve Banks were discouraging the use of coin-counting machines for gold:

The use of gold coin in machines for counting money has proved that there is quite a serious abrasion of the coin … in our country as well as in Europe, the use of gold coin as currency in the hands of the people is disappearing. The public does not want to carry gold coin…[6]

To Mint managers, the appearance of a coin was important to maintain public confidence. Bright, abrasion-free coins were highly desired by customers, and banks were quick to condemn scuffed or “dinged” pieces. Only minor coins were normally counted by machine after 1900, until production of silver coins became so large by 1934 when automation had to be used for everything except dollars.

The U.S. Mint continued to Tyler’s counting boards for gold coins through 1933. But newer technology, demanded by the immense quantities of coins required for commerce, rendered counting boards obsolete.

This short video shows how a modern coin counter works:

* * *

Notes

[1] The earliest flat counting boards were intended to count an exact quantity of coins based on filling the board’s surface with coins of one denomination. For example, to count 100 large cents, a square outline 10 times the diameter of a coin was drawn on a flat board. Thin strips of wood, the exact thickness of one coin, were tacked along sides of the square. This produced an area of 10×10 coins on each side, thus equaling 100 large cents.

[2] Rufus Tyler, Deceased, by Philos B. Tyler, Administrator. “Machine or Apparatus for Counting Coin, etc.”, Specification of Letters Patent No. 2,320, dated October 11, 1841.

[3] RG104 E-216 Vol 6. Invoice dated July 20, 1843, from Elizabeth Tyler to R. M. Patterson.

[4] RG104 E-229 Box 42. Letter of transmittal dated December 16, 1896, to Director from Treasury Supervising Architect containing original agreement dated October 31, 1844, from Estate of Rufus Tyler to William E. DuBois for United States Mint.

[5] Wilson, Charles Rivers. “The Mints of the United States”, The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal, November 1854, 407–10. Edited for clarity.

[6] Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. “Use of Coin-Counting Machines”. Circular letter issued November 21, 1917.

* * *

The post Counting Coins at the U.S. Mint: Roger Burdette appeared first on CoinWeek: Rare Coin, Currency, and Bullion News for Collectors.

This article provides a valuable glimpse into the surprisingly complex history of coin counting at the U.S. Mint. It’s remarkable how such a seemingly simple task evolved alongside advancements in coinage technology.

The ingenuity of Rufus Tyler’s counting board is noteworthy. It’s a testament to how even small innovations can significantly impact efficiency. The fact that the Mint paid licensing fees for its use underscores its value.

The detail about the Federal Reserve’s concerns regarding coin abrasion and public perception of circulated gold is quite revealing. It highlights the importance of maintaining the aesthetic quality of coinage.

The contrast between the manual methods of the past and modern automated counting machines is striking. It really showcases the journey of numismatic handling through time.